The Next Best Job in Opera if You’re Not Onstage

Last weekend, I heard a very interesting piece on WNYC ‘s informative program, “On the Media”. This episode was part of their “Day Jobs” series.

I tuned in halfway through the program and was entranced by a young woman’s beautiful voice speaking about opera. Thanks to online streaming (!), I was able to listen to the entire 9 minute segment on opera surtitles. The young woman’s name is Lily Arbisser, and she is a soprano. More on Lily momentarily.

Auto correct just corrected “surtitles” to subtitles. Our friends at Wikipedia tell me that “surtitle” is a trademark of the Canadian Opera Company. Research has lead me to a very interesting article about the “birth” of surtitles, found on the COC website. Here is a comment from an opera-going couple, Michael and Linda Hutcheon:

Going to the opera once meant a lot of work: first, you had to read the libretto (and often in translation); then you had to listen to recordings (vinyl, of course); then you had to listen to the recording with the libretto; then you were ready. All of that changed in January of 1983. Our date with a one-act, two-hour violent domestic squabble in German was accompanied by something brand new—a running translation projected across the top of the proscenium. SURTITLES™ had been invented for the COC’s production of Richard Strauss’s Elektra. What would have been quasi-incomprehensible without the above preparatory work became a riveting drama in real time that kept us on the edge of our seats. Despite the rear-guard disapproval of some conservatives who saw themselves as opera “purists,” SURTITLES™ quickly spread around the world, making the art form newly accessible, no matter one’s language limitations. SURTITLES™ are now a significant part of what makes ours a “golden age” of opera.

I recall when the surtitle “craze” first started. I was living in NYC in the 1980s, and the powers that be of the Metropolitan Opera were adamantly opposed to such a thing. At that time, surtitles were projected onto the prosceniums of most opera houses that elected to use them, and God deliver the sacred Met golden curtain from being besmirched with LETTERING. It was assumed that anyone who loves opera, and spends a pretty penny on tickets, would have done their homework and come to the theatre with full knowledge of the story and understanding of every-single-word in a non-English libretto emanating from the singers’ throats.

Well, here is a confession. I have performed about a dozen operas professionally, and I learned inside and out, word-for-word the scenes I appear in as well as those of the other characters in those scenes. But…I saw no reason to learn word-for-word what Micaela and Don Jose are singing in their Act I duet from Carmen. Carmen is not on stage with them, so why bother? Of course, I was well versed in the dramatic arc of the opera, as well as how characters other than mine influenced the plot.

Slowly but surely, the Met relented when it realized what a boon surtitles would be to opera patrons. Let’s face it, even if an opera singer is warbling in English, unless he or she is singing in the mid-range of their voice (the “speaky” range), it’s rare that a singer’s every sung word will be heard in a 3,000 seat theatre, no matter how good the acoustics.

But the Met came up with a very unique solution to the somewhat distracting “titles-above-the stage” dilemma. Back-of-seat digital screens were installed where translations of the opera on stage could be accessed in several languages (English, German, Japanese, among others).

I have found these titles extremely helpful, even for operas that I know well, and especially for lengthy Wagner operas. My only issue is that one’s focus is changing constantly from stage to screen…your eyes adjust to the action on stage (either with glasses or binoculars), then you need to look down to the small screen in front of you (about, say, 14 inches from your face). I was constantly removing or adjusting my glasses in order to read the titles

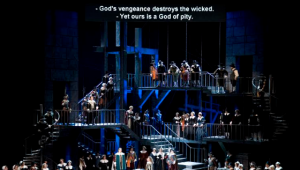

These days, surtitles, which are more commonly referred to as supertitles (because they are almost always projected on the proscenium above the stage), appear in the most remote of regional opera houses.

Here is another blurb I found online about Surtitles:

Surtitles, also known as supertitles, are translated or transcribed lyrics/dialogue projected above a stage or displayed on a screen, commonly used in opera or other musical performances. The word “surtitle” comes from the French language “sur”, meaning “over” or “on”, and the English language word “title”, formed in a similar way to the related subtitle. The word Surtitle is a trademark of the Canadian Opera Company. Source: Wikipedia

So, back to On the Media’s “Day Job” series. I enjoyed this 9-minute segment for many reasons, but chiefly because the interviewer did not constantly interrupt Lily with questions and comments. It was 90% Lily speaking in detail about her job running titles for the Met. One cannot assume, as I did, that opera titles are automatically programmed in advance. No, they are monitored by the title runner who sits in a small booth observing the live opera on stage via a small screen. Lily carefully watches the singers live, as they are performing, and when she sees that a certain line is about to be sung, she says “GO” to the technician who sits at the computer and releases the translation onto the digital screens on the back the seats. With me so far?

As Lily says, it is very important that an opera singer be the “GO” person because only a singer can anticipate, by facial expressions, posture, or the onset of sound, when exactly the translation should appear in order to be in synch with the titles appearing on the thousands of screens in the theatre.

There were a number of audio examples of this synchronization, such as recordings of scenes from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte and Verdi’s Otello.

I reached out to Lily for photos of herself in the booth, and also to inquire how she got this job. Here is what she told me: “I got the job by a mix of timing and ability, I suppose. I happened to get introduced as a freelance supertitle caller to the head of Met titles a few months before someone retired and so he called me for an “audition”, in which I called titles for selections from 5 operas. I remember Makropulos Case, La Boheme, Cosi fan tutte. Luck and having the right skill sets got me in the door. My first season I ran Rigoletto, Parsifal and the entire Ring Cycle. So it was a whole lot of Wagner :)”.

Right on, Lily. As I learned from your website, your beautiful lyric soprano would not necessarily be considered a “Wagnerian” voice, but you now probably know more about the Ring Cycle than some of us who DO sing Wagner!

This is one of the most fascinating and vitally important aspects of experiencing the art form in the modern age we live in. And it has certainly brought to the attention of millions the magical world of opera.